Development of Rusty-Recommender: Part I - Similarity Functions

In the last post, I promised to pursue ML in Rust. I want to do this in a more applicative way: by building a recommender system in Rust from the ground up. We call it rusty-recommender; and I will document every step through a series of posts on this blog.

We’ll make a library and not a binary application. We’ll use Rust’s unit testing capabilities all trhroughout the process. We’ll make use of linear algebra and other mathematical libraries, but we won’t use any machine learning libraries, such as rusty-machine.

Rusty-recommender won’t be restrictive. It will provide the user with utilities to create their own system.

For educational purposes and to save steps, we will be very linear in our code. But in the next part, we’ll fix this.

Initialization and Version Control

After installing Rust, choosing an IDE (mine is VSCode – But if you have money to buy CLion, go for it) I initialize the folder structure using cargo:

cargo new rusty_recommender --lib

After that, we create a new repository in our favorite Git host, or self-host, I go with Github but honestly renaming master to main creates a big issue for me. So we add the remote origin:

git remote add origin <remote_url>

And then:

git add A

git commit -m "initial commit"

git push origin main (or master)

Then start coding!

Crates

We need two libraries for now:

- nalgebra for linear algebra

- sdset for set operations

We tell Rust that wwe wanna use these crates by editing Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

nalgebra = "0.23.2"

sdset = "0.4.0"

You can call these libraries from anywhere:

extern [cratename]

use crate::{module}

Today’s Goal: Implementing similarity Functions

As I’m writing this, there are loads of content-based systems, collaborative-based systems, hybird systems, and demographic-based systems. Almost all of them rely on similarity functions to compare two people’s or item’s ratings, likes, visits, etc.

What is a similarity function and is it used in a recommender system?

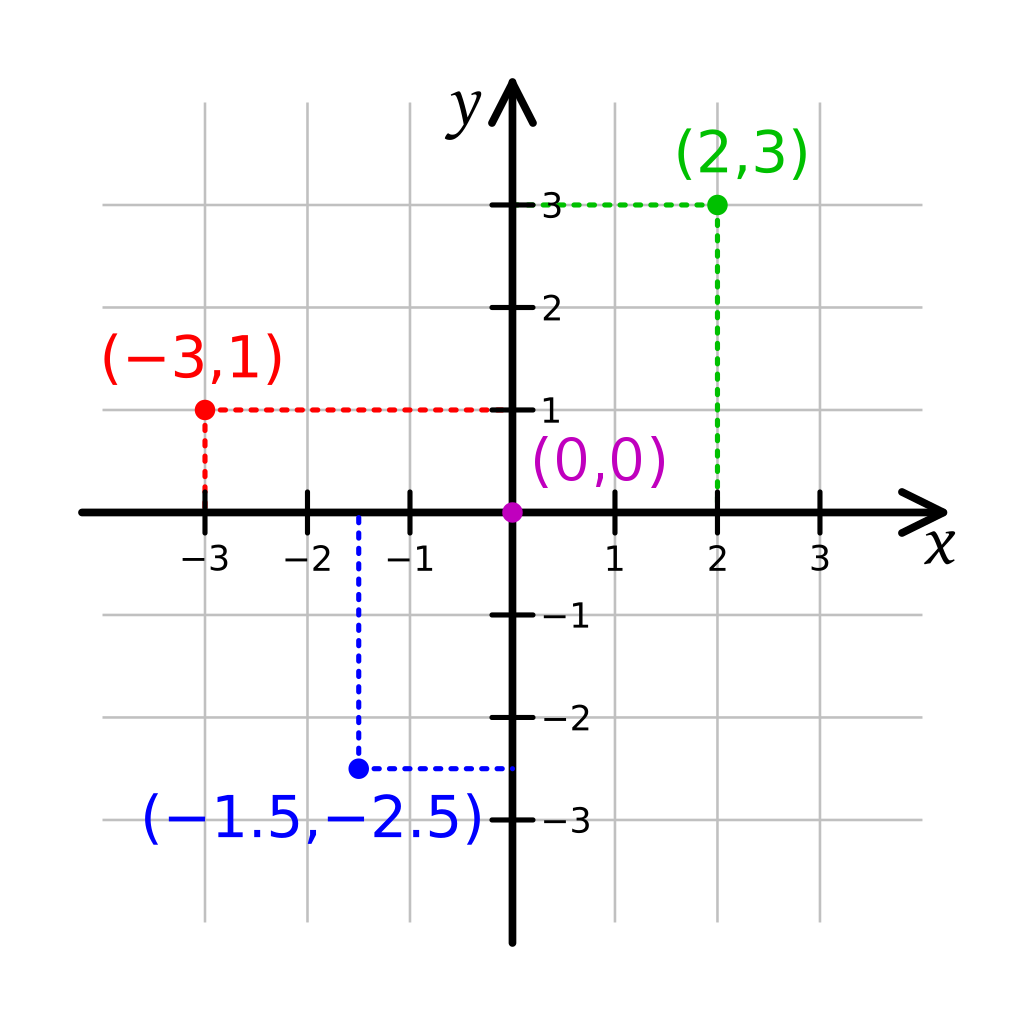

similarity systems calculate the distance of numbers from each other in various ways. Distance, as in, if the two numbers were points on the Cartesian coordinate system, similarity would be calculated by using the various functions we use to calculate the distance between these two points.

Image: Cartesian coordinate system with some points spread around

Image: Cartesian coordinate system with some points spread around

similarity functions include Jaccard similarity, L-p norm similarity, Cosine similarity, and Pearson similarity.

In the first part of this series, we wish to implement the similarties. We’ll use traits and structs. We’ll also explain the equations for each function.

Make a file called sim.rs and enter these lines into it. Done.

The Generic Struct

In the previous post, we said that structs in Rust are kinda like structs in C. They are named tuples. This name thing gives us the ability to use generic types when defining the type of variables that a struct holds.

Here, we wish to calculate the similarity of a set of numbers, and generate a set of similarties. However, we’re not sure a set of what? i64? u8? f32? Or even a group of these? So we’ll use generics:

struct similarity<T> {

a: Vec<T>,

b: Vec<T>,

}

Where T is the type of struct. We don’t need to specify the type when we initialize the struct. The type will be inferred.

let my_sim = similarity {a: vec![2.4, 2.3, 1.3], b: vec![2.1, 2.1, 1.4]}

Here, the Rust compiler infers that T is f32. Note: Types have to be the same. a and b can’t be of didferent types. But this is rarely needed.

The Generic Trait

Traits are akin to interfaces in Java and C#. They contain a set of functions, a set of traits, if you will, that the struct will display.

trait SimTrait {

fn new<T>(a: Vec<T>, b: Vec<T>) -> Self;

fn jaccard_sim(&self) -> Option<f64>;

fn cosine_sim(&self) -> Option<f64>;

fn manhattan_sim(&self) -> Option<f64>;

fn euc_sim(&self) -> Option<f64>;

fn pearson_sim(&self) -> Option<f64>;

}

We use <T> with new() because as we said, types will be inferred. The return type of all the similarity functions is f64 because they could be fractional.

Option<T> is a generic enum which wraps the return value into itself, and lets us give two options to the object user: None or Some(). We’ll see how it works later.

Now, let’s implement each function, separately.

Jaccard similarity

Jaccard distance calculates the similarity of two sets, it’s basically uses set theory to calculate the ratio of the size of set, and size of a subset.

It is defined as:

Where A are two sets. The numerator is the number of people who liked both items (the intersections), and denominator is the number of people who liked either one item, or the other (the union).

We told you to add the sdset library. Now you’ll see why. First, we have to import the libary:

use sdset::duo::OpBuilder;

use sdset::{SetOperation, Set, SetBuf};

Note: Every code you see below shall be enclosed within fn jaccard_sim(&self).

Then, we turn the a and b into sets:

let a_set = Set::new(&self.a)?;

let b_set = Set::new(&self.b)?;

Let’s dissect this code. Set:: denotes that we wish to use the Set module, and new function from it. It’s no differnt than what we’re trying to do with new in our trait. Then, we add references to a and b through self because remember, the argument of this function is itself, invoked like this:

let sim_jacc = my_sim.jaccard_sim();

The ? operator is a shorthand for unwrap(). It basically unwrapes the valid values from the returned Option<T>, and it does error handling as well. It’s equivalent to:

Set::new(&self.a).unwrap();

We then calculate the size of union, and the intersection:

union_len = OpBuilder::new(a_set, b_set)

.union()

.to_vec()

.len();

intersection_len = OpBuilder::new(a_set, b_set)

.intersection()

.to_vec()

.len();

We have to convert them to vectors first because sets are basically slices, and slice size is unkown at compile time.

We then return the value as a float:

intersection_len / union_len

Notice, no semicolon.

The entire function is (we’ll implement it later):

use sdset::duo::OpBuilder;

use sdset::{SetOperation, Set, SetBuf};

fn jaccard_sim(&self) -> f64 {

let a_set = Set::new(&self.a)?;

let b_set = Set::new(&self.b)?;

union_len = OpBuilder::new(a_set, b_set)

.union().to_vec()

.len();

intersection_len = OpBuilder::new(a_set, b_set)

.intersection()

.to_vec()

.len();

intersection_len / union_len

}

L-p norm similarity

L1 and L2 norms are also called Manhattan Distance and Euclidean distance respectively. The difference between them is the difference between finding the distance a taxicab takes in Manhattan, an the distance a rocketship takes from earth to the moon.

L1 norm is defined as:

L2 norm is defined as:

I briefly talk about these two in my book, which is currently being written (I’m taking a sabbathical from it to write this post). Join my Discord server to download the latest draft.

Using these norms, we can define L1 and L2 similarity as:

Results of these functions is a value between 0 and 1, depending on the similarity.

To calculate the L1 similarity, we simply:

fn manhattan_sim(&self) -> f64 {

a_min_b = self.a.iter()

.zip(self.b.iter())

.map(|x, y| (x - y)

.abs())

.iter()

.sum();

1 / a_min_b + 1

}

Simple, right? L2 similarity would be a bit more difficult:

fn euclidean_sim(&self) -> f64 {

abs_squred = self.a.iter()

.zip(self.b.iter())

.map(|(x, y)| ((x - y).abs()).pow(2))

.collect();

1 / (abs_squared.iter().sum() as f64).sqrt()

}

Here, we did something similar to list generators in Python using zip, map and collect. map basically takes the results of iterations and applies a lambda function to them. Here, the function is abs then pow. We then sum up this vector, and take its square root after converting it to f64. Rust doesn’t have an square root function for integers.

Cosine and Pearson similarity

Let’s remember trigonometry from high school. Imagine a unit circle with a right triangle formed between the X axis and the perimiter:

Now you see what sine and cosine are, clearly. Cosine similarity is an extension of Euclidean norm, where we use the dot product of two vectors, defined as:

So we define Cosine similarity as:

Keep in mind that later, we’re going to introduce a normalizer to our arsenal. Because most websites use different scales for their ratings, and someone could use this for visits and clicks, which makes it even more succeptible to error if we don’t normalize the value. We’ll talk about normalization in the upcoming parts.

First, we import nalgebra’s Vec1 module:

extern crate nalgebra as na;

use na::{Vector1};

We then convert Rust’s Vec to nalgebra’s Vector1:

let vec_a = Vector1::new(self.a);

let vec_b = Vector1::new(self.b);

we then compute the dot product:

let dot_p = vec_a.dot(veb_b);

We then calculate the L2 norm of these vectors:

let a_norm = vec_a.norm();

let b_norm = vec_b.norm();

And we return the result as:

dot_p / (a_norm * b_norm)

Finally, we’re getting close to the nd.

Pearson correlation coefficient

PCC is defiend as the covariance of two variables devided by the product of their standard deviation.

I’ve done a profile on expected value, variance and standard deviation in my book, The Machine Learning Codex. Join the Discord server to download the latest draft.

PCC is denoted by Greek letter rho and is hypothesized as:

And covariance is defined as the expected value of each random variable minus the mean of the set (basically, its norm, as we’ll see in the future posts) so PCC can be redefiend as:

We can finally expand this equation into:

We start off by calculating the means:

let mean_a = self.a.iter().sum() / self.a.iter().sum();

let mean_b = self.b.iter().sum() / self.b.iter().sum();

Now we calculate the covariance value:

let cov = self.a.iter()

.zip(self.b

.iter()).map(|x, y| (x - mean_a) * (y - mean_b))

.collect()

.iter()

.sum();

Now the variance of each (it’s standard deviation squared) and then take its square root to get the standandard deviation:

let std_a = self.a.iter()

.map(|x| ((x - mean_a).pow(2) as f64))

.iter().map(|x| x.sqrt())

.iter()

.sum();

let std_a = self.b.iter()

.map(|y| ((y - mean_y).pow(2) as f64))

.iter()

.map(|y| y.sqrt())

.iter()

.sum();

We finally calculate the PCC as:

cov / std_a * std_b

We’re done with this, finally! But we haven’t made an impl block yet. This is easy, and would be done in the next part of the series a few days from now.

The problem of linear code

This code we just wrote is extremely linear. Linear code is no problem in Python scripting, but in programming, it’s highly discouraged. However, I find making too many functions when I just wanna apply it twice, in one tutorial, an extremely moot point. In the next chapter, we’ll de-linearize the code, create an impl block, and learn about matrices in Rust and go further into making a recommender system.

I’m writing a book, as I said, and I would be glad if you download the latest draft from Discord and gimme your opinion.