The Wonderful Rabbithole of 6502-based Gameboards: A Journey with Rodnay Zaks

6502 Game Boards

People who follow my blog know that my hobby is retroprogramming, especially 6502 Assembly. This breed of Assembly was not necessarily limited to MOS Technologies 6502 Microprocessor only. Other variations of 6502 used it as well.

6502 Assembly has only 56 instructions. Most devices using this CPU connected various interfaces to its bus, and programmers triggered them by using the specific memory registers in the memory map. Most these memory registers were in page 0.

Imagine the SID chip, Commodore 64’s oddly able and awesome audio chip. In C64 memory map, addresses $D400-$D7FF are designated for the SID chip. If you wanna know the capabilities of this chip, just listen to this hauntigly beautiful version of Castlevania OST.

The way a memory address was triggered was this, load a value to the Acclumator (the A register, something that every Von Neumann machine must have) — then store A onto the memory address.

lda #$00011100 ;load the binary representation of 28 onto A

sta $D400 ;store A onto memory address $D400, written in zero page notation

Now, let’s store 3 values that are stored in the stack ($0100-$01FF) onto the SID chip, using the X register (index register):

_loop:

lda, x $0100

sta $D400

cpx #3 ;compare x to decimal 3

bne _loop ;branch to _loop if not equal

We can use the Y register if we also wanna increasingly store into $D400-$D400 + decimal(3) addresses. No, there’s no Z register.

Now that you’ve got a clear understanding of 6502 CPU and its Assembly language, let’s talk about “game boards”.

Game Boards

Game boards of the early 80s were the ancient world’s equivalent of Aurdino boards or Raspberry Pis. They were small computers with a simple LED display and some inputs in form of switches — along with a simple beep-boop sound module. They had a tape player that acted as the storage. Here’s a picture taken from 6502 Games by Rodnay Zaks, a book which we’ll use extensively in our quest to learn about these creatures:

There existed more intricate versions though. If we take the effort and venture into Google, we’ll find many things, among them is this, with a much better display and some other interfaces:

What we can understand is that these game boards didn’t have a discerning standard. There were numerous variants, with various interfaces connected to the bus. But the ones we’ll be focusing on are the ones that Mr. Rodnay Zaks talks about.

But who is Rodnay Zaks?

Rodnay Zaks, the Author of “6502 Games”

Rodnay Zaks is a French-born American authoro of many books, most of them concerning 8-bit microprocessors such as Z80 and 6502 variants. He is also the founder of independent computer book publisher Sybex and served as its CEO until it was taken over wby John Wiley & Sons in 2005.

He has a PhD in Computer Science.

it’s safe to say that Rodnay Zaks is way better at us, and way more skilled at us, in computing. He’s served most of his long life teaching people programming. He’s never called himself an “influencer’ and he’s never wasted his time on Twitter. Truly, if we are looking for people to serve as our role models, people like Mr. Zaks come to mind.

Personally, I love Walt Disney, and I think of him as a role model. But I’m not as crative as him, and I’ve long accepted the fact that i’ll never be as big as Disney. But I CAN be someone like Rodnay Zaks. I’m going ot go on a tangent here and propose this idea: “Choose someone whom you can be as your role model”. I aspire to be Walt Disney, but I WANT to be Rodnay Zaks.

Planning a Simple Game

In order to write a game with these game boards, you must plan ahead. Planning ahead is lost on some people. I’ve seen web developers, data scientists, game developers, and even graphics programmers who just fire up their IDE and start programming. That’s wrong. That’s bad methodology. You must plan ahead.

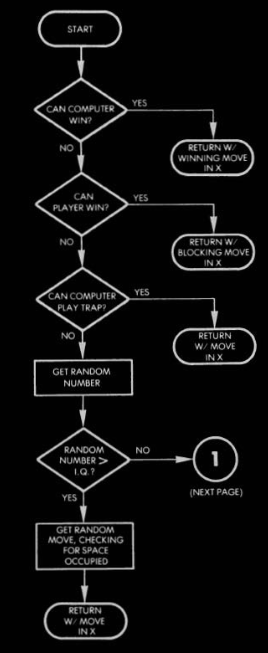

One of the simplest ways to plan ahead a game is a flowchart. Here, we’ll see one for Tic-Tac-Toe:

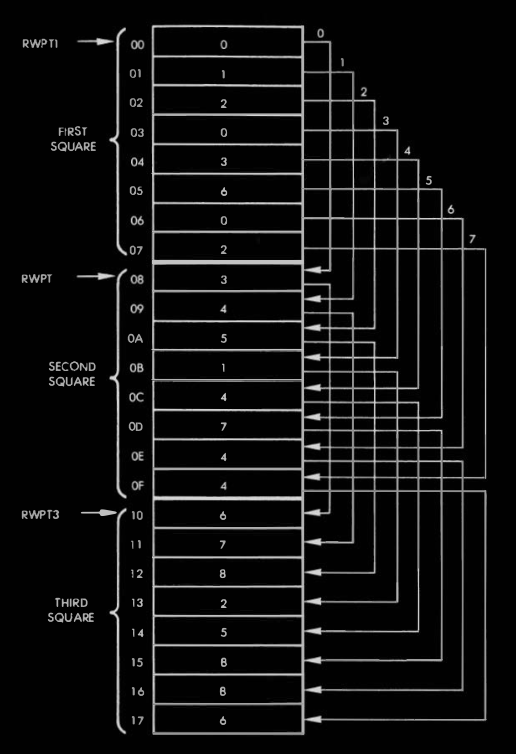

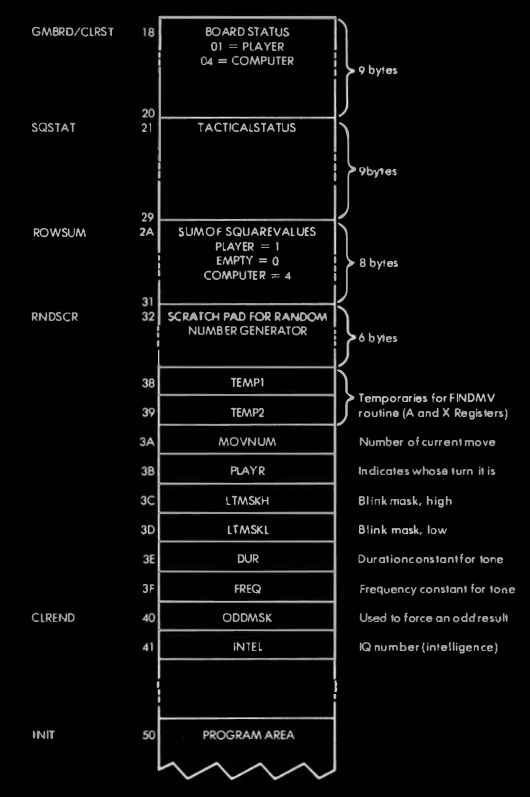

Then, we must plan ahead the memory use. It’s not something that’s done in the modern world. But when only a handful of memory addresses are at play, it makes sense to map the memory use:

Data Structures

Oh, we modern programmers are so spoiled when it comes to data strucutres! Need hashmaps? Just import it. Need graphs? Just import it. We have reached an impass where out-of-box data structures fit most of our needs, especially in dynamically-typed languages. But in 6502 Assembly, we must design a custom data structure that would fit our needs. It’s no different than designing a class in C++ or Java. But in a much more limited way, and memory is at stake here.

For example, for the aforementoned Tic-Tac-Toe game, Mr. Zaks used a linear table with three entry points to store the eight possible square alignments on the board. The table is organized in three sections at RWPT1, RWPT2, and RWPT3. These are memory addresses in which RWPT stands for raw pointer — each of them being an address for the LED matrix. These fall under high memory. But what is high memory?

High and Low Memory

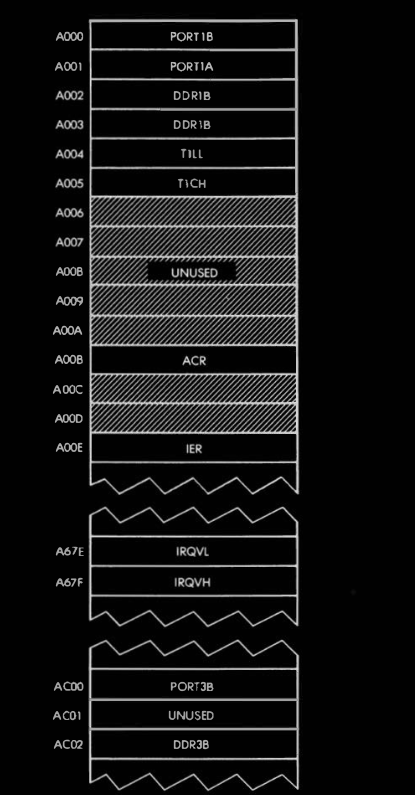

High memory locations are the addresses reserved for input/output devices. Low memory locations are the ones reserved for the game logic itself. We must plan aheaad the use of high and low memory in a 6502 game. Let’s view how Rodnay Zaks make two charts for them.

High memory:

And low memory:

Downloading the Book

The book is available on Archive.org. Here.

If you ask me, when reading this book, you should make the whites black – just as I did. This is what I do with all the low-quality scans.

Emulating a Game Board: Commodore 64 0r Apple II?

Now the main question you may ask here is “Chubak, I don’t own a game board, how do I implement these codes?” to which I answer “The codes will run on any 8-bit microcomputer which uses 6502 or variants, use them!”

But which microcomputer?

When it comes to 6502 programming, you have two viable options. Commmodore 64 and Apple II. The way it works is, you download an command-line application called a Cross Assembler — for C64 I recommed a cross assembler called KickAssembler — and after you’ve assembled the code, you run it in an emulator like VICE.

I’m just informing you that Apple II is a viable option, but I’m not recommending it. Apple II was far from a game machine. With limited graphical abilities. Nobody bought Apple II just for gaming. But people did buy C64 or C128 to play games.

Another option, which your mileage may vary in it being viable, is the NES. Using assemblers such as NESASM you can simply make a .nes file and run it on an emulator. There aren’t any codes available for any of the NES games, but fitting them into NES’s hardware isa challenge that will enable you to make a full-fledged NES game.

I hope you’ve had fun reading this post! Chubak out.